“Today we face another great civilizational question: How can we create a morally cohesive and politically functional democracy amid radical pluralism and diversity?” —David Brooks, The Election is Happening Too Soon

In Sheltering Each Other I wrote about the meitheal and how this practice of mutual support literally means in Irish “linked to the other.” This spirit of interdependence is also found in le cheile (“together” or literally, “with each other”), which, as I explored in What’s Love Got to Do with It?, is used in Irish to refer to your life partner (husband, wife, or spouse) and even your in-laws. For example, máthair chéile, literally “mother together,” is how you say “mother-in-law.” These are not people you are bound to just via land, money or legal obligation (as the etymology of the English words suggest); they are literally the people you choose to be together with.

Reflecting the importance of together-ness, in the Irish language dictionary Teanglann, there are more than ten pages (500+ phrases) using céile. Some translate directly into English, for example “praising each other” (ag moladh chéile). Not all are collaborative or harmonious (Tá siad le chéile arís means both “they are together again” and “they are at each other, fighting, again”). Yet I consider it significant that “together” turns up this often in Irish. In contrast, there’s barely two pages for “mother,” a significant word in any language. Consistent with this “togetherness,” in Irish there is a high level of relationality. You don’t listen “to” someone or something; you listen “with” (le). In Irish, even the act of listening has relationality written into it.

Relationality occurs not just in Irish words and phrases; it’s implicit in the very structure. Verbs and nouns change form in Irish, depending on person, number and case. That’s pretty straight forward and common to most Indo-European languages, as is gender for words (male/female; there used to be neuter too in Old Irish but that’s archaic now). Yet in Irish, as in other Celtic languages, the initial consonsants of words also change form; these mutuations are “an important tool in understanding the relationship between two words and can differentiate various meanings.” For example, the word bean, “woman,” changes to bhean or mbean depending on gender, case, and if used with a definite article. The pronunciation also changes with each mutation. These mutations happen to hundreds of words—words, like “woman” that you use everyday.

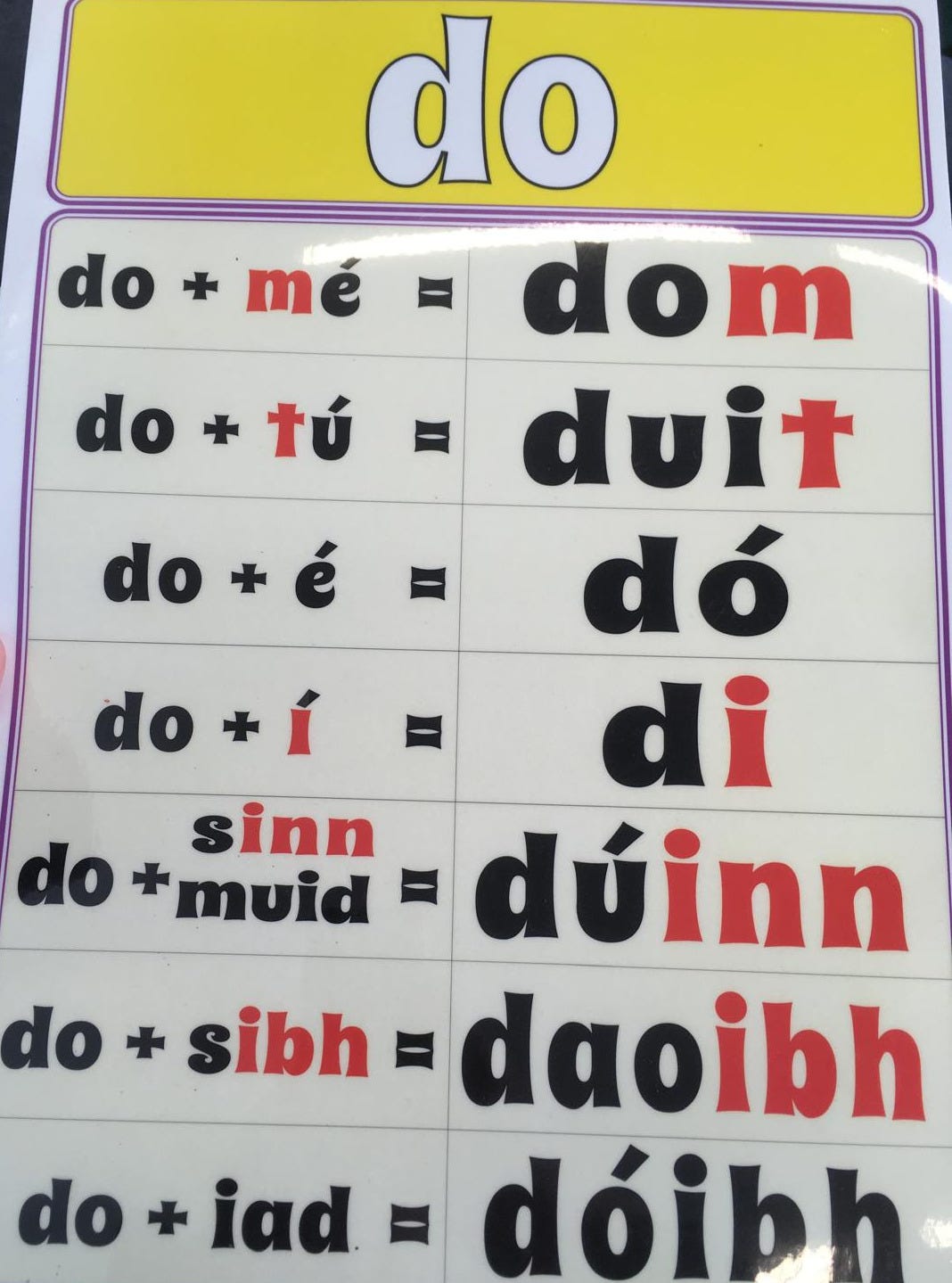

In Irish, prepositions also conjugate. For example, if you want to say “for me” it’s dom; “for you,” duit; “for him,” do. Here’s a chart, for example, showing all the conjugations for do (“for”):

Again, these kinds of dramatic changes don’t just apply to some prepositions; all prepostions conjugate (change form) in Irish. At first, I found this confounding; it’s bad enough learning verb conjugations! Yet now I find it sublime. In this Irish language view of the world, we not only have impact on others or other things; we are equally changed by being in relation/ship to (and as Irish would say, with) them. As I explored in A World Pulsing with Life, this reflects the indigenous Irish belief that all life has consciousness and is alive.

Inflected prepositions are also common in Middle-Eastern languages. Yet taken with other aspects of Irish, I see this as part of a larger pattern where relationality and interdependence are so core to a cultural way of being that it’s literally “written into” the very bones of the language. This can also be seen in the vocative case in Irish (where again names and words change form to clearly show a person is being addressed) and in Irish numbers, where there’s a completely different system for referencing human beings than when counting or referencing things. For example, you say “two cats,” dhá chat, or dhá theach, “two houses,” but simply beirt when referencing “two people.” Since there’s a separate number system, you don’t need to use the word daoine (“people”); it’s already clear you’re referencing human beings. This is highly efficient (in some ways); it’s definitely highly relational.

“The libraries groan with books diagnosing our divisions, but where is the new social ideal? Where is the set of values that will motivate people to put down their phones and dedicate their lives to changing the world?” —David Brooks, The Election is Happening Too Soon

All humans value community. As mammals, we are biologically wired to be social, empathic and relational beings; we seem to instinctively know (perhaps from archetypal memories of sheltering together for warmth and physical protection) that we find “safety in numbers”—in community, with companionship. This is what the story of Adam and Eve, regardless of all the gendered and misogynist readings available, ultimately tells us: that humans in a primal way need each other; we desire companionship and mutual support. We thrive on relationship. Research repeatedly shows the negative health impacts of loneliness; those with healthy social networks and intimate relationships (life partners, meaningful friendships, and friend circles) are happier, healthier and live longer.

Yet the complexity of these most basic needs are also not lost on me. Recent research also shows the dangerous side of empathy and the desire for belonging. There has always been this “dark side” of human relationality, where the “enemy of my enemy is my friend.” J.D. Vance’s contemporary spin on this is, “I think our people hate the right people.” As David French points out, from this perspective, “community is more important than ideology,” “trust is tribal,” and debate is less about “disagreement and more a betrayal.” Marshall Rosenberg, the creator of Nonviolent Communication, saw how the basic need for companionship and belonging can give rise to destructive thoughts and actions, like the desire for vengeance. Ironically, retribution can be seen as a distorted desire for empathy—a longing for another human being to fully understand your own pain and suffering.

“Fear and anger can make any person more vulnerable to charlatans. We all need community and are understandably reluctant to alienate those closest to us.” —David Brooks, The Election is Happening Too Soon

This kind of “negative partisanship” can be seen at full force in the world today. It is safer, more familiar and more comfortable to stay with what we know, especially when we gain a sense of community (identity and meaning) in those beliefs and within our cocoons. Holding onto belonging (at all costs) especially becomes important in a world that’s topsy-turvy and in turmoil. When overwhelmed and worn down by the news and world affairs, staying with (and within) your “tribe” becomes even easier and more urgent. Depleted and low-resourced, for most of us it takes too much energy to climb out of our rabbit holes to consider something challenging or new. Nationalism, especially when practiced by those with geo-political (i.e. structural) power, is perhaps the most dangerous form of blind urgency for tribe and belonging.

“Our nation still lacks the sense of social and psychic safety that would allow us to have productive conversations across partisan difference. We still lack a national creed or a national narrative that would give us common ground among competing belief systems.” —David Brooks, The Election is Happening Too Soon

I long for a world of genuine (rather than reactive) relationality and interdependence—where we are fully aware of how we impact and depend on others, including other species and the planet. The Irish language is an exquisite dance of interdependence: words and pronunciation change form moment-to-moment to convey who is speaking with whom, what is happening where and when. Both listening and responding require present-moment awareness and attunement to the relationships and needs at-hand and also to the whole. How relationship comes alive in the details of the Irish language offers me hope that, as human beings, we are capable of a relational complexity that I think we will need to survive—and thrive.

Some questions to consider…

How do you experience and create community?

What does interpendence and relationality look like, everyday, in your life?

Where do you hit internal boundaries or limits around connecting and extending to others? What needs are you meeting when you do so?

Slán for now,

Dian, i mBaile Atha Cliath (in Dublin)