Fáilte! Welcome!

A chairde (Dear friends):

First, summer solstice is a week away! That’s when three paid subscribers—yes, three!—will win a copy of Effie Brush’s delightful art-prose book We will Never Be Together. You have an excellent chance of winning! Subscribe or give a gift subscription here (it’s only about 75 cents per week). Thanks for your support.

Now, today’s edition of An Éifeacht Ghaelach. Táim beagáinín mall an tseachtain seo ach seo mé! (Am running a bit late this week—half a day—but here it is!)

Full of awe

In North America, “Awesome!” is superlative. It means “great” or “wonderful,”—like go hiontach! in Irish. That makes sense. If something fills you with awe, even “some” or a little (i.e. (awe-some), it must be wonderful. Yet how does “awful” (full of awe) mean the opposite—”very bad” or “terrible'‘? It took me going to a workshop to really get how awe works—and how both these meanings (awful and awesome) co-exist.

“The experience of awe is the feeling of being in the presence of something vast that exceeds our current understanding of the world. It is the feeling of being overwhelmed by something larger than the self.” —Psychology Today

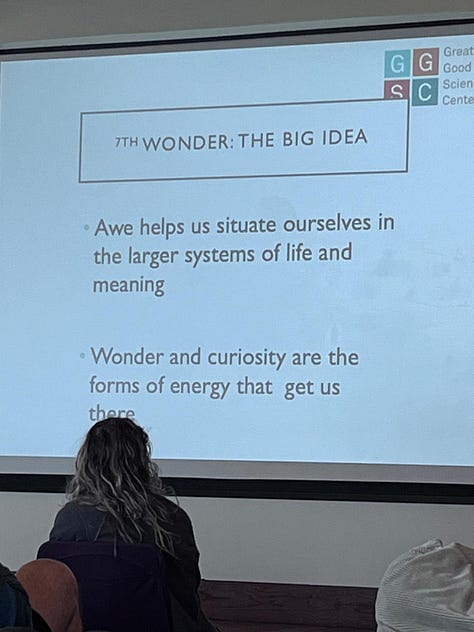

The greater good

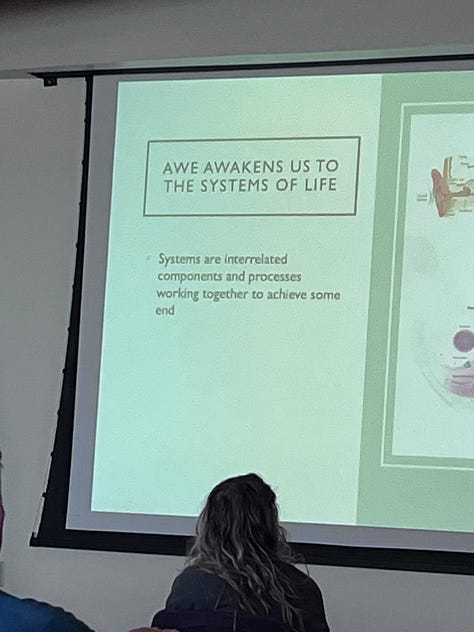

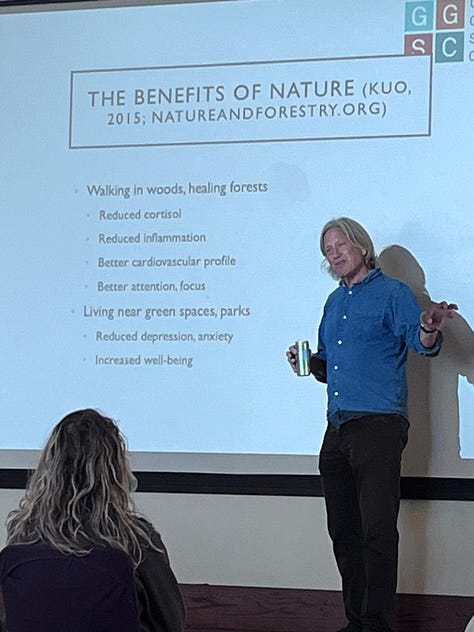

The workshop I attended was with Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, director of the Greater Good Science Center, and author of the book, Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life. Keltner explained that, until about fifteen years ago, scientists focused on emotions like "fear and disgust, which seemed essential to human survival.” (Awe) Yet connecting us to something bigger than ourselves, awe is now seen to play “a key social need, fostering cooperation and shared identity.” These qualities are necessary for our collective evolution and survival. (Awe) In fact, similar to empathy, awe is another “positive” feeling seen as crucial for human beings:

“People in awe are more likely to show generosity, become less individualist, and emphasize a greater sense of connection to others and the world. In moments of awe, we shift from the sense that we are solely in charge of our own destiny to the feeling we are part of a community. When we are less focused on ourselves (our own goals and needs), we have more mental capacity to notice others and what they may be experiencing.” (Psychology Today)

Ultimately, awe motivates us to take action that is good for the natural and social world around us. It generates inspiration, creativity, new insights and the creation of art, music, and religion. Not surprisingly, it’s also good for our bodies: it soothes our immune system’s inflammation response! (Awe)

“The experience of awe can have a profound impact on our mental health, by allowing us to put our anxieties into perspective. When we are in the presence of something vast and indescribable, we feel insignificant, and so do our worries. The experience of awe lifts us out of the ordinary practical thoughts that dominate our daily lives. And it allows us to have inner peace.”—Psychology Today

The complexity of darkness

I especially became interested in awe about six years ago when events in the world began to weigh on me: climate change, mass extinction, and, in particular, the plight of the vaquita porpoise. The vaquita is the only warm-water dolphin and the smallest in the world—with beautiful Mona Lisa eyes. As a result of illegal fishing nets, she is close to extinction. There are currently six to eight remaining. While working to raise awareness of the vaquita’s plight, I had “the sadness of the world upon me” (tá brón an domhain orm). I saw that to keep going in the world (which increasingly seemed—and seems—very dark) that I needed more wonder and awe.

At the workshop, Keltner explained that awe comes not just from experiences that are positive or beautiful—such as seeing a great work of art or a sky bursting with stars. Awe is an expansive and at once humbling quality. Like those Asian paintings where the human being is a tiny part of a very big landscape, awe at once connects us to something bigger than ourselves while giving perspective on our (relatively small) place in things. Experiences that we might consider “negative”—such as death or adversity—when faced with courage—equally invite in awe.

“Awe is mysterious. How do we begin to quantify the goose bumps we feel when we see the Grand Canyon, or the utter amazement when we watch a child walk for the first time? How do you put into words the collective effervescence of standing in a crowd and singing in unison, or the wonder you feel while gazing at centuries-old works of art?”— Dacher Keltner

These qualities of awe unlock the linguistic puzzle of why “awesome” (some awe) and awful (full of awe) sound similar but are opposites. The current meaning of “awe” is a feeling of “amazement, fear or reverence.” (WikiD) I personally had missed the fear part—I had thought “awe” was all about amazement. True to this full meaning, it comes from Middle English eiful (“inducing fright or terror, terrible”) and from Old English eġeful (“fearful; inspiring awe”). So awe is complex. The key element is that it brings us out of ourselves; it connects us to the bigger picture. While human ignorance and greed is killing the vaquita, it is awe-some for me that other groups, such as Sea Shepherd and Earth League International, are working heroically (often risking their own lives facing cartels) to save this beautiful, rare species.

Rooted

Connecting me to something bigger, I love how the Irish word draíocht—which can mean wonder, awe, magic, amazement and enchantment—goes back directly to the druids. It comes from Old Irish druídecht (“secret lore and arts of the druids”). (WikiD) Even today, it can still refer to druidic art and druidism. Similar to the original meaning in English of “awe” (to induce fright or terror), uafás in Irish means horror, terror, as well as awe, wonder and astonishment (and can also mean a vast or astonishing number or amount) and also uamhan with the triple meaning of “fear, awe, dread” (Teanglann). These nuanced and deeply-rooted words in Irish (going back several thousand years) remind me that magic and enchantment also have elements of fear. This again is how reverence, awe and fear connect: we are witnessing (and participating in) forces greater than ourselves.

I know that I am not alone in needing magic, wonder and awe. Even before scientists started researching it, myths—which can often be scary and horror-ible but always inviting in that which is bigger-than-ourselves—illustrate this primal human need. Jungians have long known this and current work, such as that of

(The Enchanted Life: Unlocking the Magic of the Everyday) explores it.The synchronicity of awe

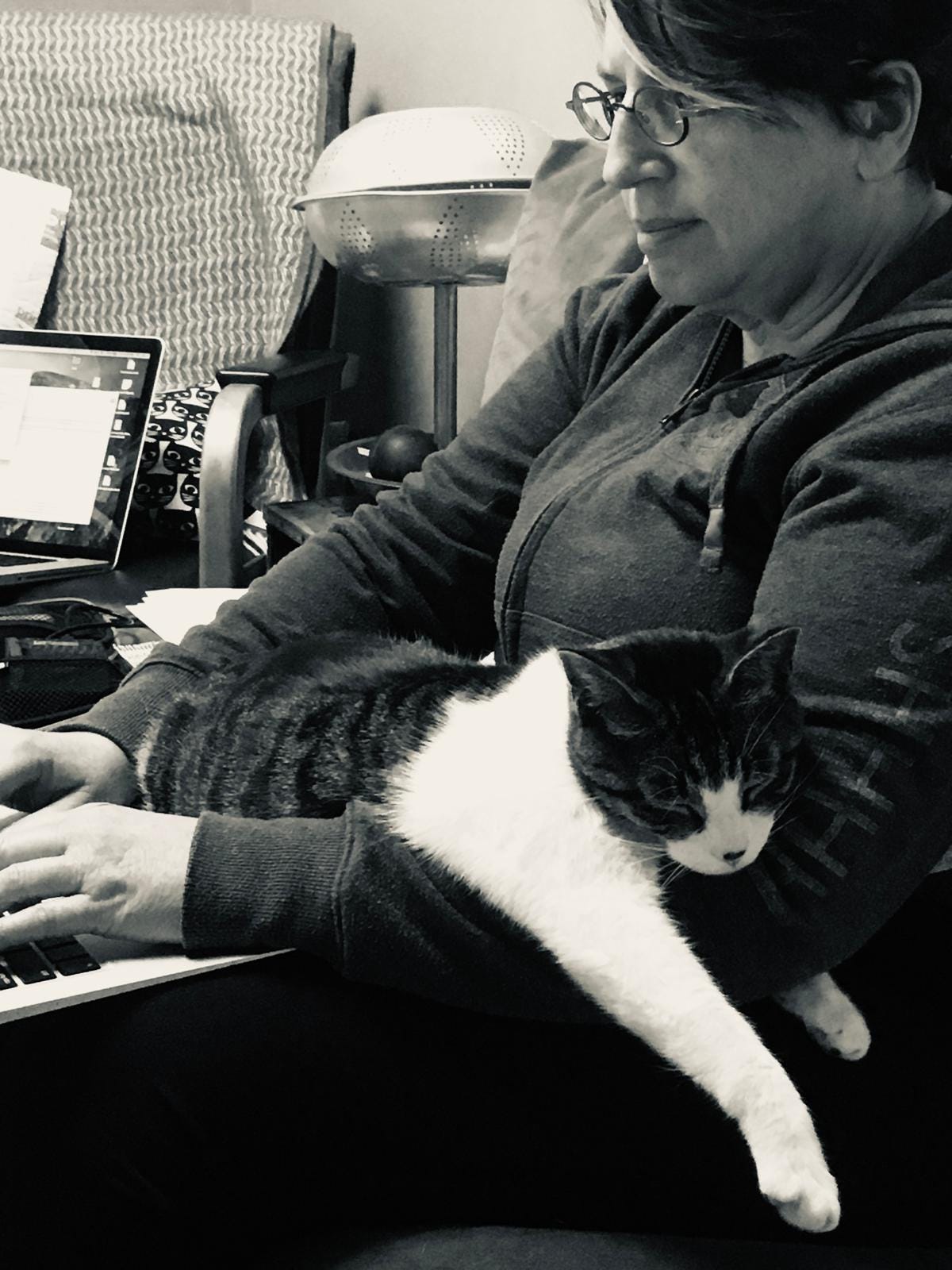

As readers know, I lost three weeks ago (at least in this realm) my beloved anam cara and familiar Séamus. Even in his passing he was my guide, opening up spirals of reverence, presence, and awe. Many of these portals started opening months and days before he left, as I was learning to more closely communicate with him (with the help of Lisa Tully). There were also increasing and awe-full moments of synchronicity. The Sunday before chuaigh sé bealach na fírinne (“he went the way of truth”), Sweet Baby James kept coming into my mind. While I had passed through the Berkshires, the song wouldn’t leave me. It then finally hit me: Séamus means James in Irish. The words are a perfect goodby. I think it was his way of telling me it was time to go:

"Ten miles behind me and ten thousand more to go… There’s a song that they sing when they take to the highway, a song that they sing when they take to the sea, a song that they sing of their home in the sky, …So goodnight moonlight ladies, rock-a-bye sweet baby James, deep dreams and blues are the colors I choose. Won’t you let me go down in my dreams?…"

Before he passed, I told him that I hoped to see him at the rainbow bridge. Nothing would make me happier than to be with him again. It was incredibly moving that when we brought his body out to the garden that a rainbow crossed the sky. For me, it was a moment of awe.

Wistful, continuing to seek magic, and grateful go bhfuil tú anseo (that you’re here),

Dian, i mBaile Atha Cliath (in Dublin)

P.S. Séamus also had an awesome sense of humor. I’ve been meaning to share a story about that. Look out in Notes for it!

P.S.S. As always, Irish words are hyperlinked to https://www.abair.ie/ga where you can hear the pronunciation in the dialect of your choice.

You can also support The Gaelic Effect and its mission by making a one-time donation by clicking anseo (here).

There are few things more awe-some as a deep relationship with an animal. The photo of Seamus on your lap brings tears to my eyes! Thank you for reminding us of the mysterious but familiar gift of awe, which is ours to receive almost every moment.

Dian, thanks for sharing your inspiring stories and thoughts. LOVE the photos of you and Seamus! With awe, hugs and gratitude...