Listening for the “Yes”

Marshall Rosenberg, the creator of Nonviolent Communication (NVC), taught a concept that is simple yet profound: that anything anyone ever says is either some form of “please” or “thank you.” While not always easy to hear—especially if the other person is shouting, if I can find “please” or “thank you” in what they are saying, no matter how hurtful or jarring—I can find a way to respond with love.

Marshall also taught to listen for the“yes” behind the “no.” Whenever someone says “no” to one thing, they’re actually saying “yes” to something else. For example, if my partner says, “No, I don’t want to go the dinner tonight,” I could interpret this as her not wanting to spend time with me or caring less about the relationship. If I’m listening for the “yes,” I can hear what she’s choosing: self-connection, choice, and rest.

Hearing “please” or “thank you” and listening for the “yes” behind the “no” do not mean we always will like what people say, how they are behaving, or the strategies they choose. We don’t have to agree or give up on our own needs. Yet listening in this way opens up space for understanding, empathy and connection—and a more satisfying and mutually agreeable outcome.

It also makes life more fun and interesting. What’s the “yes” hiding out here? What pearl am I missing? Looking for what’s beautiful in people—even when hard to see—improves my own headspace and quality of life.

“…on the whole, […] the primary function of the mysterious powers governing the universe is not to exact obedience, punish, and destroy but rather to give.” Rianne Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade, p. 20

What’s fascinating for me is how often the Irish language is consistent with NVC principles. I first became aware of this in organizing the 2022 Ireland IIT (International Intensive Training). While the event was being held as Bearla, in English, it was crucial to me that all basic NVC materials (the four core steps of NVC and the feelings and needs lists) be translated into Irish, as Gaeilge. Especially given Ireland’s history, where Irish was largely destroyed as a result of Britism imperialism, it was unacceptable for me to hold an event in Éirinn, in Ireland, without materials available in the Irish language.

Not content to have translations just on sheets of paper tucked away in a binder, I printed out large format versions of feelings and needs as Gaeilge and posted them around the retreat center. Each morning in the opening circle, I shared one aspect of the Irish language consistent with NVC. These intersections proved very inspiring for the group, especially Irish participants. Given that Irish is one of the oldest languages in Europe with roots going back thousands of years, it illustrates a point that Marshall often made: that NVC is the natural language of human beings.

With your willingness

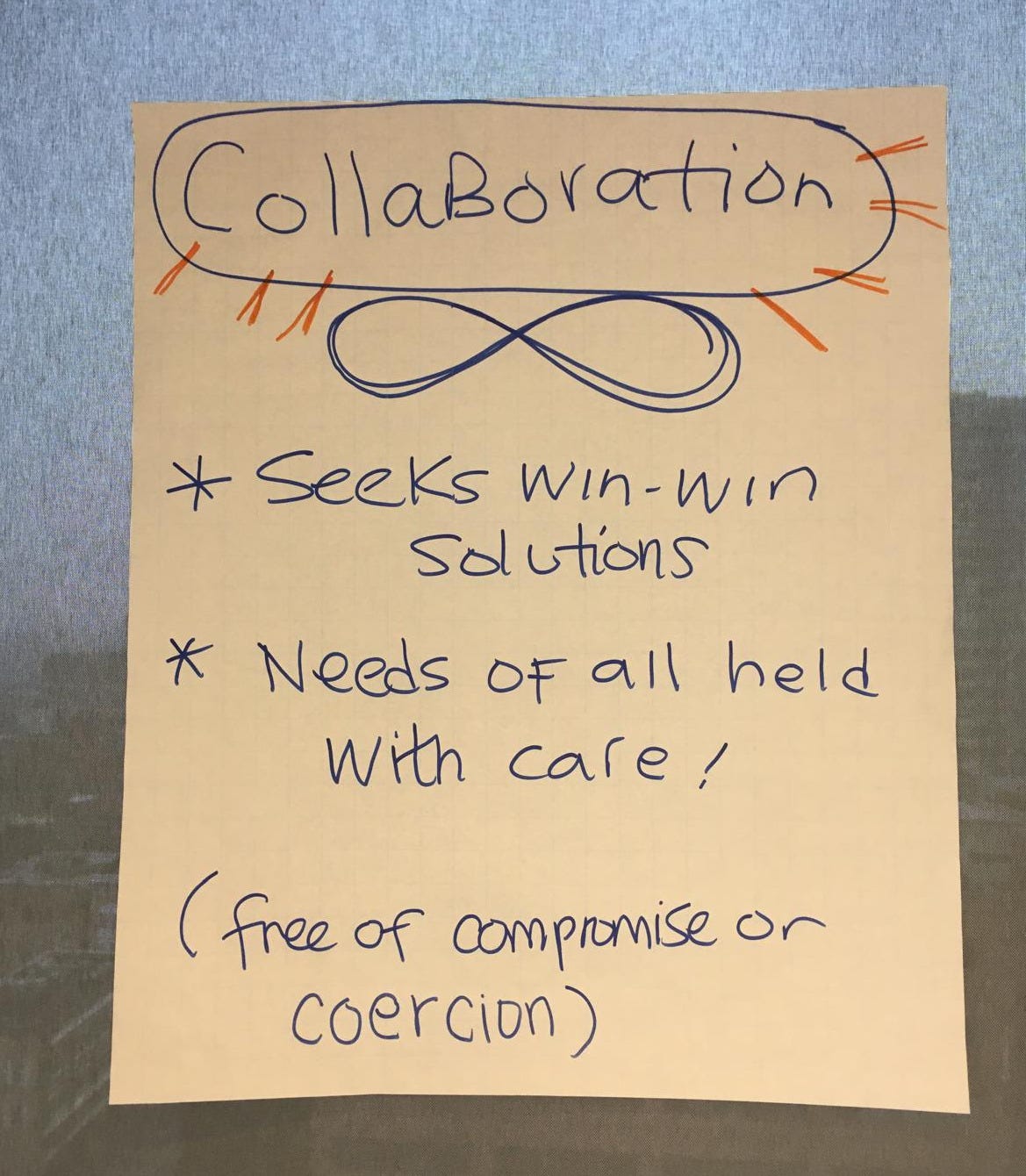

Hearing the “yes” behind the “no” goes with a larger NVC concept of making requests rather than demands. To ground us in this intention, when making requests in NVC there’s a specific tag line we start with: “Are you willing to …?” Even if you don’t use this exact phrase (you could also say, for example, “Are you ok with…” or “Does that work for you?”), the tagline acts as a place holder and reminder to make a genuine request where we’re open to hearing “no.” This points us in the direction we want to head: towards openness, curiosity and collaboration.

The word “please” in English originally held a similar intention. From Old English, “to be pleased,” it comes from the French, plaisir, such as in avec bien de plaisir, “with much pleasure.” When I was in college, I learned a French drinking song, Chevaliers de la Table Ronde, that invokes this joyful plaisir in the context of enjoying some good wine with friends. S'il est bon,… J'en boirai jusqu'à mon plaisir (“If it’s good, I’ll drink my fill—i.e., until I’m pleased”):

Based on this, it seems that “please” ended up in English as a shorthand version of, “If it pleases you…” In other words, don’t do anything from obligation or pressure; don’t go down the treacherous road of resentment or regret. Does it give you genuine plaisir? Is it pleasing for you? “If you please” or “if it pleases you” may sound overly formal and polite but it’s ultimately about willingness. Marshall raised the bar even further: he spoke about joyful giving and receiving. When making requests, we want the action to be joyful for both parties, with the joy of a little child feeding a hungry duck. Who is delighted more—the duck getting to eat, or the child delighting in feeding it? (Or the knights enjoying that wine?)

Ní peaca guí a iarraidh. “It’s not a sin to ask.”

If it pleases you…

It’s fascinating to me that this concept of willingness is still front and center in the Irish language. You don’t need to dig up etymology or old French drinking songs (as fun as that is). In Irish, the way you say “please” is literally, le do thoil, “with your will” or “willingness.” Toil means “will,” “desire,” “inclination” or “wish.” Le do thoil then is almost the exact, verbatim NVC request: “Are you willing…?” In Irish, it’s not just a concept in a communication manual or training. It’s how Irish speakers actually communicate every day when saying “please”—or the closest poor translation of it into English. Perhaps it’s just more common in Munster, but in Buntús Cainte, “please” is even más é do thoil é, literally, “if it pleases you.” It’s not just le, “with” your will or desire; my desire (toil) is conditional—and so dependent—-on yours. This use is not unusual or highly formal in Buntús Cainte: people use más é do thoil é when buying butter in a shop.

Maybe for native Irish speakers le do thoil and even más é do thoil é are used so often everyday that they don’t even think about what these words literally mean anymore. It might be a throw away phrase, a formality, as much as “please” now is in English. Depending on the tone of voice and how it’s used, “please” in English can even communicate the very opposite of a request (“Can you PLEASE shut up!). Irish speakers may also say le do thoil at times when communicating in fact a judgement or demand. But I love that “willingness” is so on the surface. I see it as a persistent reminder to engage the other, to collaborate. It’s speaking NVC without even trying to—and it’s simply part of the Irish language.

“The old view was that the earliest human kinship (and later economic) relations developed from men hunting and killing. The new view is that the foundations for social organization came from mothers and children sharing." — Rianne Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade

Living with joy

Again, Marshall often said that Nonviolent Communication is our natural language as human beings and that we simply need to remember it. It’s striking that the indigenous language of Ireland is so consistent with that forgotten language of compassion. It suggests to me, as Rianne Eisler shows in The Chalice and the Blade, that early humans did live in a very different way in relation to each other—with much more mutuality, respect, harmony and peace:

“Just as some of the most primitive existing societies, like those of the BaMbuti and !Kung, are not characterized by warlike cavemen dragging women around by the hair, it now appears that the Paleolithic was a remarkably peaceful time. And just as […] the city of Troy was not Homeric fantasy but prehistoric fact, new archaeological findings verify legends about a time […] when humanity lived in peace and plenty.”

As such:

”[…] under the new view of cultural evolution, male dominance, male violence, and authoritarianism are not inevitable, eternal givens. And rather than being just a "utopian dream," a more peaceful and equalitarian world is a real possibility for our future.” Chalice and the Blade, p. 73

It’s also compelling for me that both Rianne and Marshall talk about joy so often; as an extension of this, Rianne talks about the “pleasure bond.” Pure joy (an expression of the sacred) is a quality of life that’s grossly underrated and little experienced in today’s world—the only place you consistently see it is an advertisements (“Enjoy X!)” and at Christmas (“Joy to the world!”).

What would a world be like of authentic and joyful giving and receiving? The meitheal and concepts of le cheile as well as le do thoil give us a glimpse into what’s possible.

Slán go fóill, by for now, and GRMA, thanks for reading,

Dian, i mBaile Atha Cliath (in Dublin)

Slán, slán